How annual hikes and satellite photos revealed dramatic changes—and what the research confirms

The View from the Timberline Trail

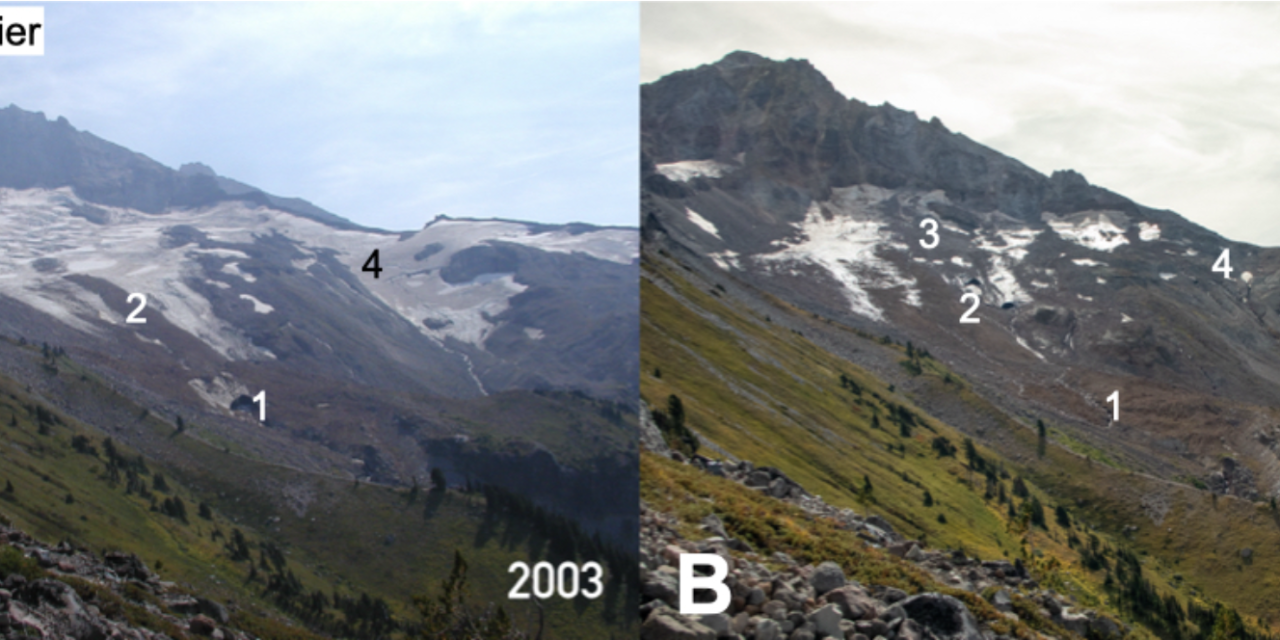

Every October since 2017, I’ve hiked the Timberline Trail around Mount Hood, looking at the glaciers at their annual minimum—when summer melt has stripped away seasonal snow to reveal the true extent of permanent ice. Year after year, the changes have looked undeniable. Glaciers seem to have retreated upslope. Ice fields that gleamed white now lie buried under rock debris. What were flowing rivers of ice have become stagnant remnants.

The visual evidence is stark in satellite imagery spanning the last decade. But seeing the change and measuring it scientifically are two different things. How much ice has Mount Hood actually lost? How do we move from photographs to precise volume calculations?

I posted some initial thoughts and quite rightly folks responded with some additional questions: some years a low snow years, the satellite imagery does a good job of showing the extent of the visible ice, but not that which is covered by debris.

I thought as the hiking season winds down I’d put some time into whether there is a more scientific and accurate way of looking at this. So i did some research.

The Challenge: From Pictures to Measurements

When you want to measure glacier volume change, you quickly realize that satellite imagery alone—even high-resolution photos taken at the same time each year—can only tell you part of the story. Images show you area: how much ground the glacier covers. But volume requires knowing thickness: how deep the ice goes and how much that depth has changed over time.

To calculate volume change, you need:

- Surface elevation data from multiple time periods (LIDAR or other digital elevation models)

- Ideally, bedrock topography data from ground-penetrating radar to understand total ice thickness

- Accurate glacier boundaries (where satellite imagery excels)

The surface elevation shows you how much the glacier has thinned. The bedrock data tells you how much ice remains. The difference between elevation measurements from different years, multiplied by surface area, gives you volume change.

This increased the challenge somewhat – I had the satellite data and started to look for LIDAR and ground penetrating or ice penetrating radar. Luckily as I started to look around I started to find a body of research that was already focused on glaciers on Mount Hood. I had already come across the work of Dr. Karl Lillquist who had a paper that highlighted the changes on Mount Hood glaciers art the start of this century. His work stopped at the turn the century – I was interested in what has happened i the last 25 years as well.

What the Research Reveals

Fortunately, scientists have been doing exactly this kind of work on Mount Hood. The results confirm what anyone hiking the Timberline Trail can see—but with sobering precision.

The Latest Findings

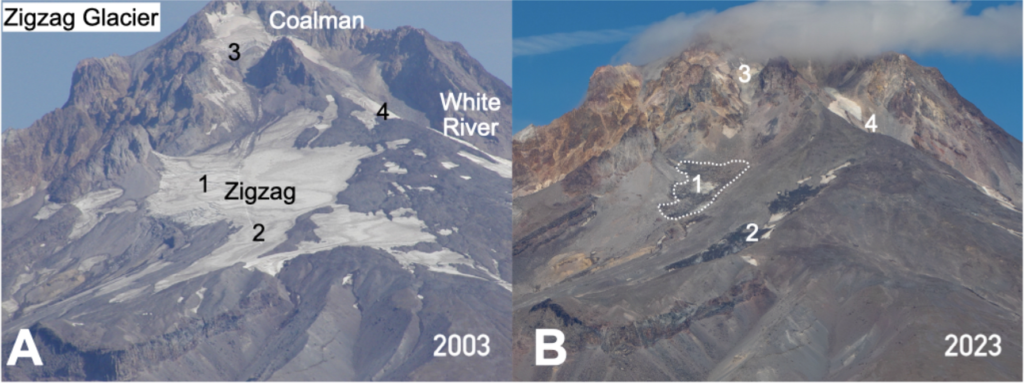

A comprehensive 2024 study published in The Cryosphere by researchers from the Oregon Glaciers Institute provides the most up-to-date assessment. “Unprecedented 21st century glacier loss on Mt. Hood, Oregon, USA” documents dramatic retreat across all of Mount Hood’s glaciers from 2003 to 2023.

Key findings:

- Mount Hood’s glaciers lost ~17% of their 2015-2016 area by 2023—in just 7-8 years

- The seven largest glaciers lost ~25% of their area between 2000 and 2023

- The rate of loss is accelerating: 2.10% per year from 2015-2023, compared to 0.81% per year from 1981-2016

- Two glaciers (Palmer and Glisan) have ceased flowing entirely and are now just stagnant ice

- Three more glaciers (Zigzag, Coalman, and Langille) are approaching stagnation

The study combined field observations with GPS measurements and satellite imagery, documenting a minimum rise in elevation of actively flowing ice of approximately 150 meters on average across all glaciers over the last 20 years. Some glaciers, like the Clark drainage of Newton-Clark Glacier, have seen their terminus rise more than 300 meters.

This paper had scientifically documented what I was seeking to do. My job had become a lot easier. It’s sobering reading. The supplemental data has some great photo comparisons from over the last decade.

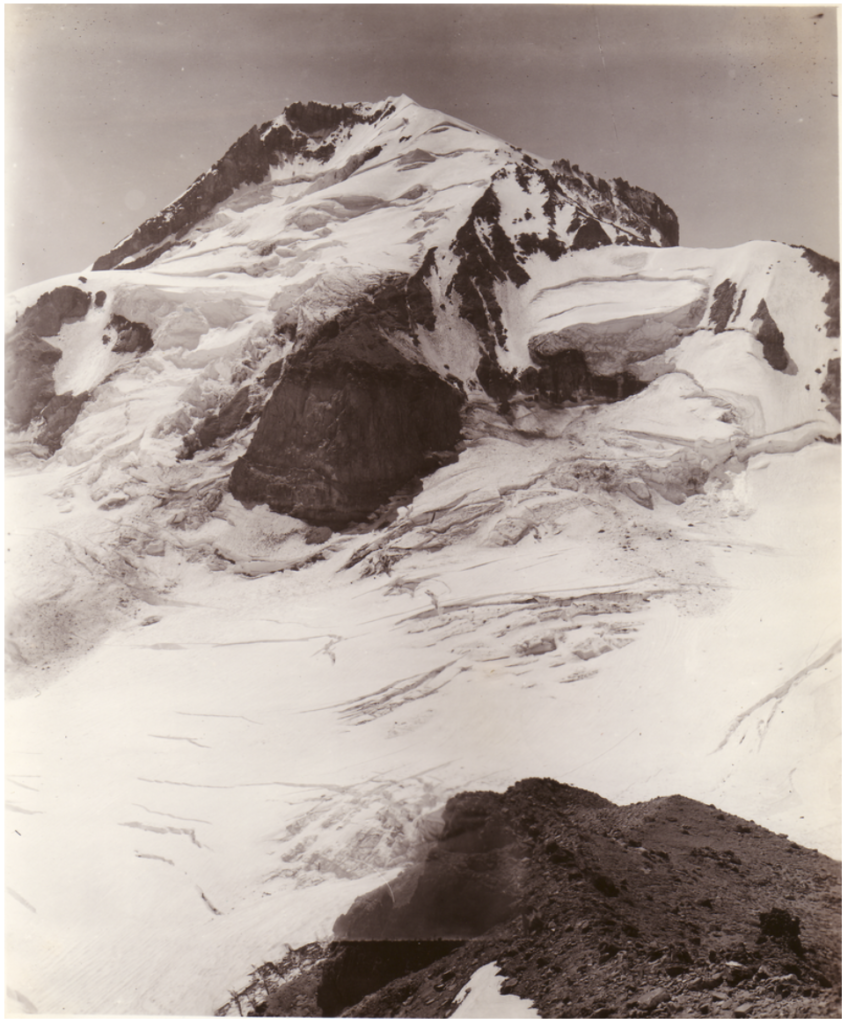

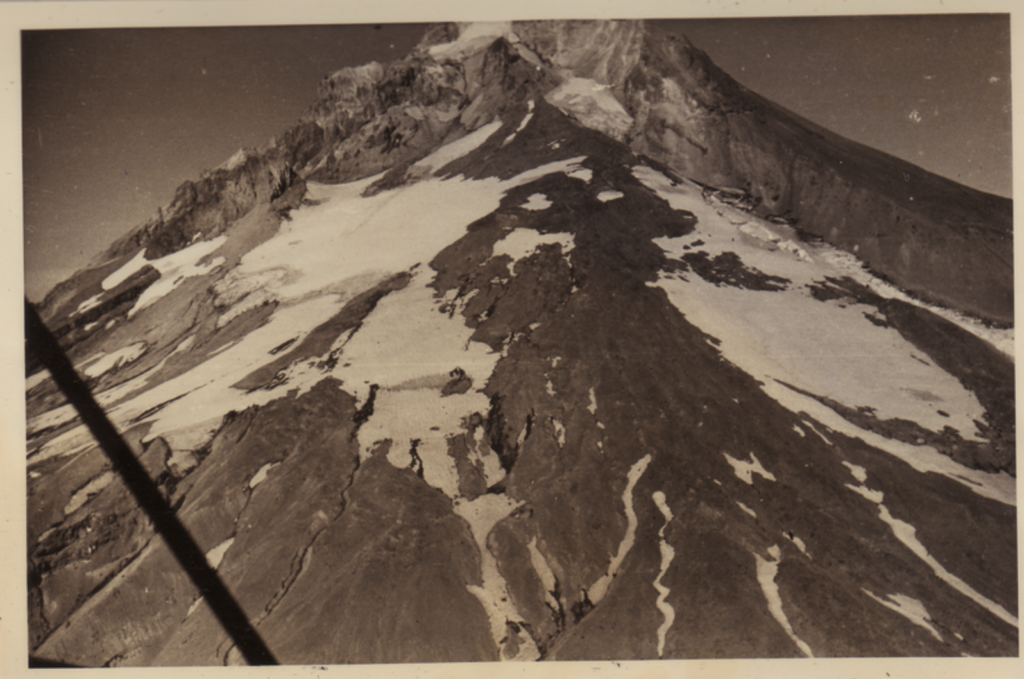

Historical Context

The researchers compared current retreat rates to historical records dating back to 1907. The conclusion is unambiguous: the 21st century rate of glacier loss is unprecedented. The current rate of ~1.07% per year (2000-2023) is:

- 1.9 times faster than the fastest 20th century rate (1907-1946)

- 3.5 times faster than the 20th century average

Since 1981, Mount Hood has lost approximately 39% of its glacierized area.

Portland State University Research

Much of the foundational work on Mount Hood’s glaciers comes from Portland State University’s Andrew Fountain and his research team. Their work includes:

- Comprehensive glacier inventories for the western United States

- Area and volume change studies using repeat LIDAR surveys

- Long-term monitoring of Pacific Northwest glacier recession

- The 2023 glacier inventory showing Mount Hood’s current glacierized area and perennial snowfields

Fountain’s research group has documented that Mount Hood’s glaciers and perennial snowfields currently cover about 13.5 km² and contain more than 300 million cubic meters of ice and snow—but this represents roughly half of what existed in the early 1980s.

The Original Ice Thickness Data

The baseline for understanding Mount Hood’s glacier volumes came from pioneering work by the U.S. Geological Survey in the 1980s. Driedger and Kennard’s 1986 study “Ice volumes on Cascade volcanoes” used ground-penetrating radar to measure ice thickness on Mount Hood’s major glaciers, creating the subglacial contour maps that established how much ice existed before the current period of accelerated loss.

Why It Matters

These glaciers aren’t just scenic features. They’re:

- Water resources: Late-summer meltwater feeds the Hood River Valley’s orchards and maintains stream flows for salmon habitat

- Climate indicators: Their retreat directly reflects regional warming—summer temperatures are now 1.7-1.8°C warmer than the early 1900s

- Ecological systems: Glacier-fed streams support unique life and downstream ecosystems

As the Oregon Glaciers Institute’s work shows, we’re not just watching glaciers shrink—we’re watching some of them die entirely, transitioning from flowing ice to stagnant remnants that will eventually disappear.

From Observation to Understanding

What started as a visual observation from the trail—”the glaciers look smaller every year”—led me to explore how this change could be measured scientifically. The answer required multiple data sources: satellite imagery for boundaries, LIDAR for surface elevation, radar for ice thickness, and crucially, repeat measurements over time.

The research confirms what the photographs suggest, but with a precision and historical context that makes the scale of change impossible to ignore. Mount Hood’s glaciers are retreating at rates never seen in the historical record, and several will likely cease to exist as functional glaciers within the next few decades.

The next time you hike around Mount Hood, what you’re seeing isn’t just scenic change—it’s the visible evidence of our warming climate, documented and measured by dedicated researchers who’ve given us the numbers behind the vanishing ice.

If you are interested here is some Further Reading:

- Unprecedented 21st century glacier loss on Mt. Hood (The Cryosphere, 2024)

- Oregon Glaciers Institute

- Andrew Fountain’s Research – Portland State University

- USGS: Glaciers at Mount Hood, Oregon

- Lillquist & Walker: Historical Glacier and Climate Fluctuations at Mount Hood, Oregon

- Glaciers of the American West

All photos are from the either the Glaciers of the American West or Unprecedented 21st century glacier loss on Mt. Hood